Pro-environmental choices are often framed as “sacrifices” but there is power and peace in aligning our actions and values.

Surrounded by chatter about making resolutions and by advertisements for all the ways a “new you!” can be purchased as a new year begins, I'm prompted to think about what has actually brought me closer to being the kind of person I aspire to be. Spoiler: the significant things haven’t been any products I’ve bought nor any new pursuit I’ve started specifically in the name of self-improvement. Instead, the slow, ongoing personal process of working out how to respond to a world on fire has been unexpectedly revealing.

This past year cinemas, academic institutes and community groups around the country have been hosting screenings of Plan Z, a short film that captures the motivations of scientists (including myself) who have become climate activists. It’s often shown alongside complementary documentaries about how we respond to the Emergency we find ourselves in - whether that’s climate denial, anxiety and/or action. I’ve repeatedly found myself thinking back to a specific moment from one of those films: it’s a moment where a student activist reflects on a protest where they’d climbed on top of an oil tanker and been arrested. They describe an unexpected sense of peace - and a relief from the often overwhelming anxiety they were accustomed to - in ‘doing something tangible’, in spite of how terrified they felt taking that action.

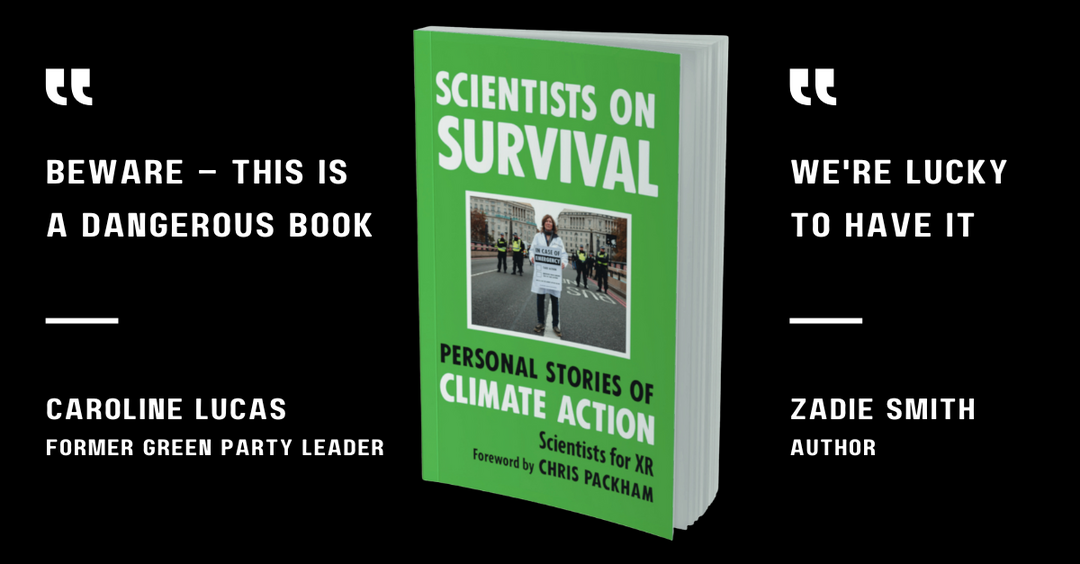

This student’s seemingly paradoxical response - to experience calmness in an unfamiliar, high stress, high intensity situation - has started to sound familiar to me. Several of the authors in our book Scientists on Survival allude to something like it. I’ve felt it myself too. In today’s world, many ‘normal’ ways of going about life conflict with values that many-if-not-most of us hold dear. It can feel impossible to do the ‘right thing’ and I often struggle encountering this in seemingly trivial daily decisions. So at those times where we act in certain ways that might look rash or radical, maybe that feeling of relief isn’t so strange.

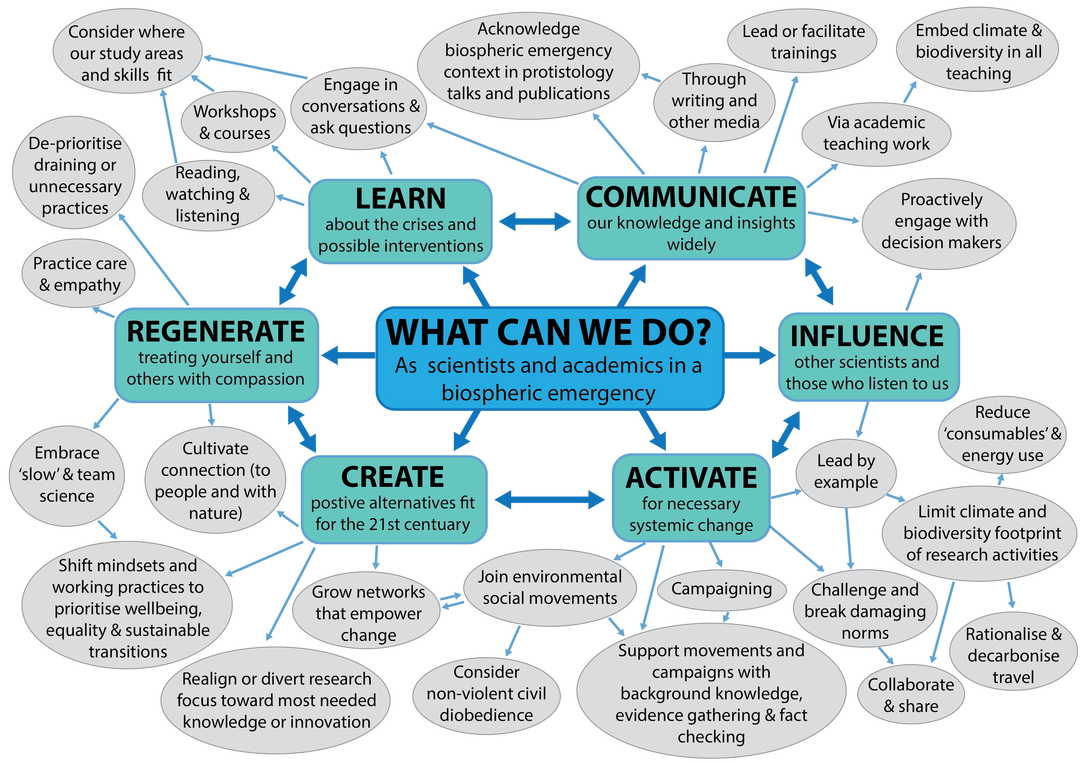

When I worked in academia I found some of these conflicts - the clashes between our stated aspirations and the realities of how we were going about pursuing them - particularly stark. Essentially I found the experience of studying a dying world in the knowledge that we were further endangering it in the process paradoxical and deeply uncomfortable*. I worked in settings where we incinerated kilos of contaminated single-use plastics every single day, where flying halfway around the world for a few days at a conference was considered a perk of the job, and where an increasing proportion of our research was financed and influenced by some of the most destructive organisations (or billionaires) on Earth**. If questioned, these kinds of behaviours were swiftly justified as necessary for, or simply an accepted and acceptable part of, advancing human knowledge… as if it wasn’t relevant that the foundations that’d allow any benefits of that knowledge to be realised (stable climate, intact biosphere, functioning societies) are crumbling.

Having left academic science behind with a heavy heart, I thought I’d feel envious of other researchers who could handle the contradictions I had tried and failed to reconcile. But whilst I did (and still do) feel some loss about the career and identity I stepped out of, the stronger sense has been one of relief. The extent to which mental gymnastics had sapped my energy and self-esteem only really became clear once I no longer needed to perform them. Lifting that weight, even though it meant inviting more uncertainty and risk into my daily life, has been freeing. We all have different levels of comfort in breaking with conventions and expectations, as well as different vulnerabilities to the associated repercussions. But I also think that more of us than we might realise would benefit on a personal level from doing so. Psychologists use the term “cognitive dissonance” to describe the often-severe discomfort we experience when holding conflicting ideas in our heads, whereas one aspiration of therapy is to foster “congruence” or harmony between how we see ourselves and how we live our lives. To me this speaks to the value of resolving the incompatibilities between our values, our identities and our actions wherever we can.

The realities of our imperilled world do not make aligning our actions with our values straightforward…but where we can do so it stands not only to make positive ripples but also to bring us joy as well as relief in the process. The narrative that acting more sustainably or ethically inherently involves sacrificing your happiness is a powerful one, but it’s often wrong. You can see this in the testimonies of people who have shifted their approach to food or travel, you can see this in the stories of activists who find purpose and community in pushing for change. The idea that evolving in line with our ideals is a noble but ultimately futile and joyless endeavour needs to be challenged, now more than ever. One simple way we can do this - and one resolution I can commit to this year - is to notice, celebrate and share the pleasure and peace we experience as we take the plunge.

*I’ve touched on this in a previous post and in the concluding paragraphs of a review article I co-wrote, and recommend this perspective article about the underlying social and psychological factors that allow this ‘double reality’ to exist in academia

** I frequently saw research funded by or conducted in partnership with fossil fuel companies, militaries or weapons manufacturers, agribusiness giants etc, or billionaire’s foundations (Gates, Bezos or Musk) when I worked in the environmental or biological sciences. See the work of the Mapping Fossil Ties project (for example) for why these relationships, however attractive they may seem in a challenging and competitive research environment, are so problematic.

Cover image credit: Paul Kelly, York, UK