Reflections on effective climate and nature communication, following the National Emergency Briefing

You might have heard or read that last month (November 2025) over 1000 influential figures across UK politics, society and culture gathered for a first of its kind National Emergency Briefing on climate and nature. Ten experts laid out the facts about the polycrisis we are in, how all of our lives will be radically reshaped by it, and the actions that will make a positive impact in response. Since June I’ve worked with the NEB team as their science adviser, which has involved collaborating on the messaging and content of the briefing, as well as working with some of the scientist speakers to increase the clarity and impact of their talks.

The National Emergency Briefing’s expert panel, fielding questions after their talks

Academics usually aren’t taught, nor really encouraged, to communicate research findings clearly, simply and impactfully. Throughout my time in research science, I’d attend seminars with reluctance and restlessness, frustrated by the all-too-common experience of learning very little from long, excessively detailed presentations that lacked relevance for most of the (often largely disengaged) audience… So nobody is more surprised than I am that it was a lecture in 2018 that marked such a clear turning point for me. It was a Thursday afternoon in the Autumn, and all 400 of the ‘postdoc’ scientists at the medical research institute I worked at were expected to attend a talk by a guest speaker, a doctor who was talking about the connections between climate and health. This was a subject I, naively, thought I already had a decent understanding of… but I was not prepared for what I heard that afternoon, when the doctor laid bare the imminent threats to our survival. I don’t remember the statistics or the graphs, but I vividly remember the moment he said he feared his own future and felt terrified for his kids’. I remember how I felt receiving the dire news over the course of that hour and how I felt when I left the room. It changed the course of my life.

Seven years later that same doctor, Prof Hugh Montgomery, was among the ten experts presenting the National Emergency Briefing. And seven years on, our prognosis is no less frightening… the lack of political and societal leadership - and the lack of proportionate, emergency intervention - means the picture is much bleaker. When we’ve needed to be stepping up en masse, empowering one another with knowledge, galvanizing and collaborating on society-wide action, we’ve instead had misinformation, denial, temptations to delay and very understandable, very human wishful thinking get the better of us. This has already, and will continue to, cost us all dearly. But in the words of another of the briefing’s speakers, food system expert Prof Paul Behrens: “The best time to act was yesterday, the second best time is today.”

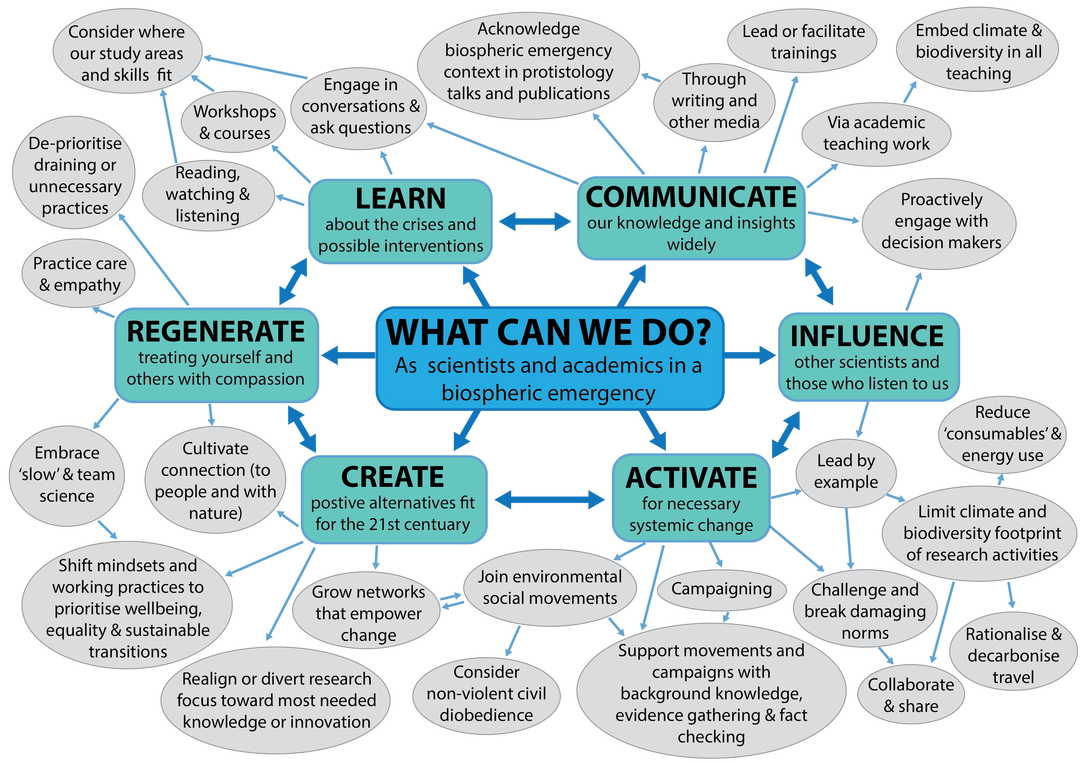

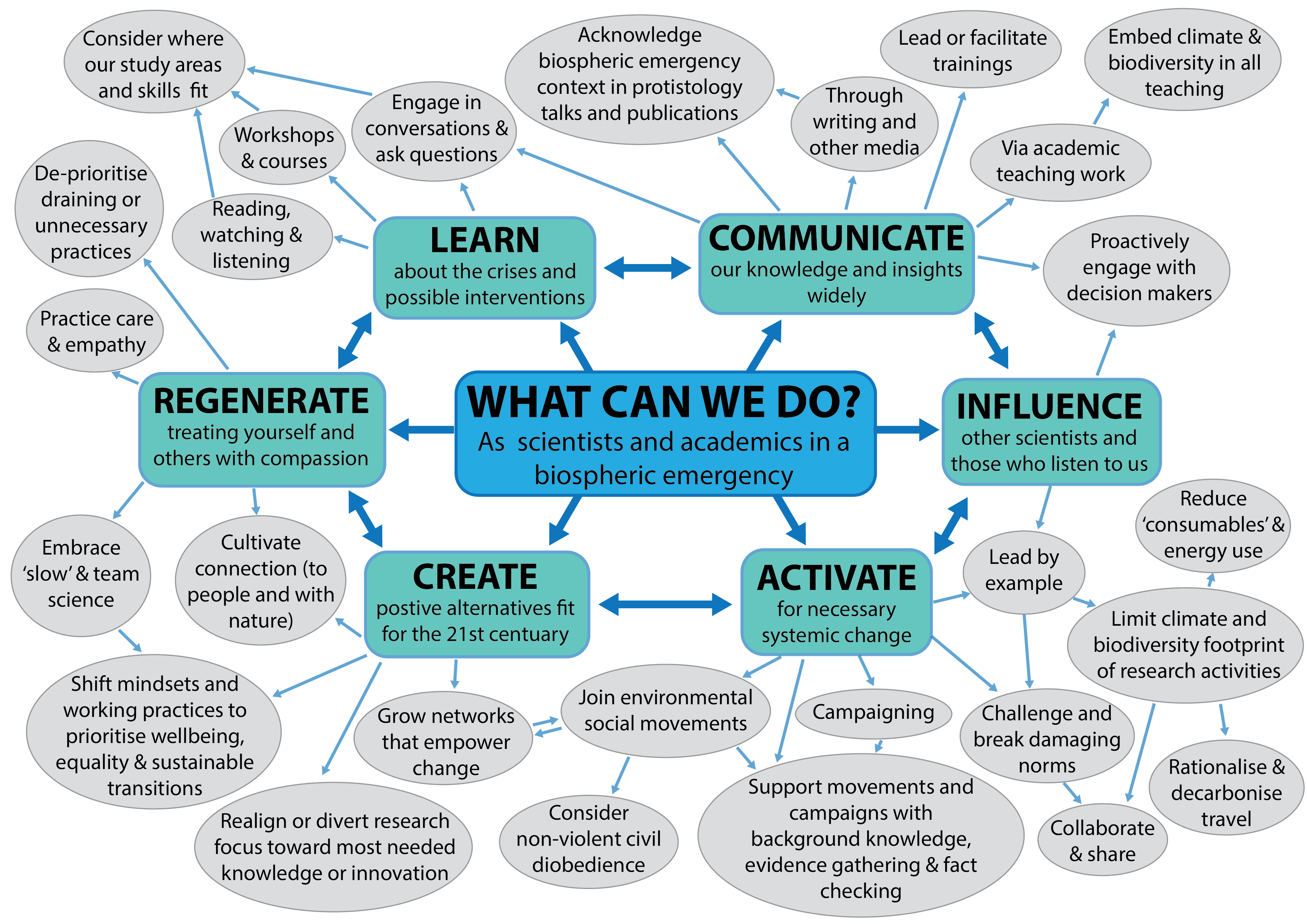

I have enormous respect for every one of my fellow academics, science communicators and activists who have taken on the often-uncomfortable yet vital task of speaking clearly and unequivocally on the Climate & Nature Emergency. None of us have a tried-and-tested formula for it: a different audience, or even the same audience on a different day, will respond differently. However carefully we do it, there will be those who criticise us - fairly, less-than-fairly, or downright maliciously. When we probably have a lot of competing pressures and demands on us, the necessary time, energy, confidence and emotional resilience can take a lot to muster. But given the escalating state of Emergency, we can’t let the difficulty and discomfort of the task stop us. Working together, sharing our knowledge openly and supporting one another allows us to face those challenges, so in this spirit, and drawing on the recommendations I made for National Emergency Briefing, here are some of the principles I use to guide my science communication.

Simplicity wins

There’s something I see as a troublesome myth in science communication: that using complicated words and visuals makes you seem more credible. In my book, seeing that someone has taken the time and thought to select the most important information and present it in the clearest, most compelling form they can is a much stronger signal to trust the messenger. The stakes are high here - if we overwhelm or confuse our audiences, we risk causing them to disengage at the expense of taking on board vital, consequential information. Here are some pointers:

- Be selective and concise: choose the most important messages your audience need to take away with them and focus on landing those well as opposed to packing everything you can into the time or length that’s available or most appropriate. You can always signpost sources of more information that you’ve chosen not to include.

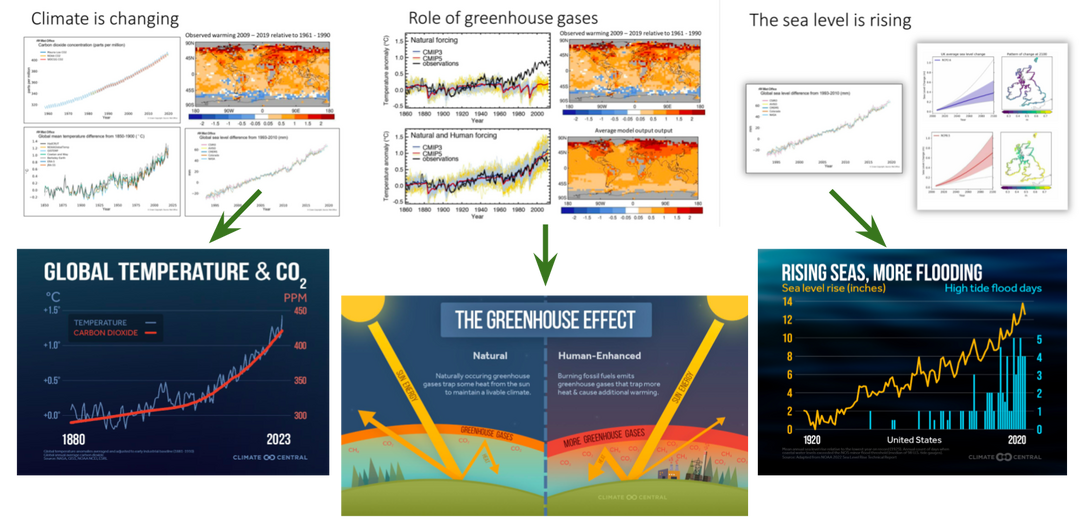

- Simplify graphics, statistics and technical terminology: Data! Scientists need it and we can be drawn to presenting lots of it to make our case. But overusing complex graphics or sharing a deluge of statistics in overly technical language might be the quickest ways to lose your audience. So make sure you choose data carefully, avoiding “number overload”, and make sure any graphs you do present are simple enough to be understood quickly.

- Emphasise key messages: You can use formatting and structural tools (e.g. subtitles in articles and clear titles on slides) to do help this. Repetition can also be useful to consolidate the most important points; providing a summary of key take-aways throughout and/or at the end is often appreciated by audiences.

Less can be more: Examples at the top are slides from the UK chief scientific advisor’s briefing to a former prime minister, and below are from Climate Central’s key facts slide deck as of November 2025. Of course different levels of detail are appropriate for different contexts and audiences, and there are situations where technical detail is important: I’ve included these to illustrate that complex information can be more immediately understandable and impactful once simplified and distilled to emphasise the core messages.

Know your audience

It would be incredibly useful and convenient if a one-size-fits-all approach to climate & nature communication existed! But in reality each specific audience and their specific context matters a huge amount to what will be most effective. Your impact will almost always be enhanced if you take the time to:

- Tailor your approach and message to align with your audience’s context, interest and what’s most likely to resonate with them. For example, you could choose examples from their “world” to illustrate your points, and explicitly join the dots between what you’re talking about and how their priorities will be impacted.

- Avoid assuming knowledge, because not feeling included or that you’re ‘not clever enough’ to understand* is alienating. Providing enough background and choosing phrases appropriate to those less familiar with the subject can be done without patronising or boring those who are more comfortable with it.

- Involve the audience (where possible). For trainings or events, engagement, interest and impact are usually increased wherever if it feels like a shared, participatory experience. I often ask the audience questions, encourage them to speak with one another, and/or include activities that mix up the format.

* Very regularly I hear workshop participants tell me that they’re ‘not good at science’ or that they don’t see themselves as very capable of understanding scientific ideas. This is often based on bad experiences at school or with poorly-pitched science communication and rarely reflects their actual abilities.

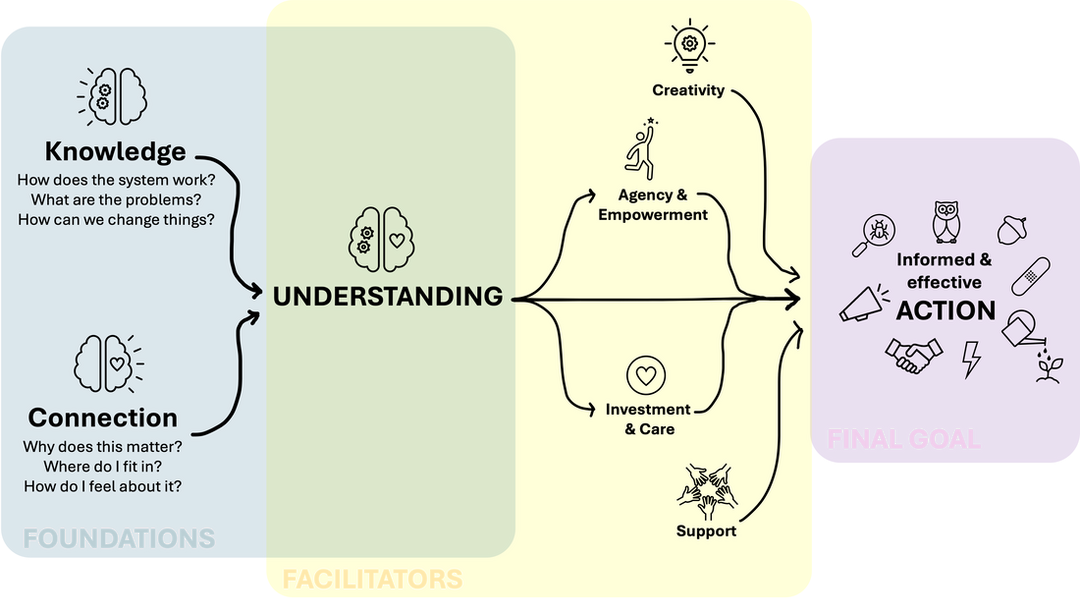

Engage with emotion

True understanding is not just about knowledge - there is an emotional component too. We can know a fact but until we feel why that fact matters to us, we are unlikely to act on it. It can feel daunting, exposing or “unscientific” (and for many people I know “un-British” too) to bring emotion into our communication… but I’d argue strongly it’s both rational and important to do so. I’ve often asked myself how much scientists’ cultural tendency to communicate in a dispassionate, “objective” way has detracted from the urgency of our messages. However I also wouldn’t generally recommend delivering the difficult realities of our polycrisis through floods of tears, however proportionate that might be. Striking the right balance allows us to convey immediacy and severity of the Emergency without compromising our clarity and credibility. Here are some of the approaches I often use to thread this particular needle:

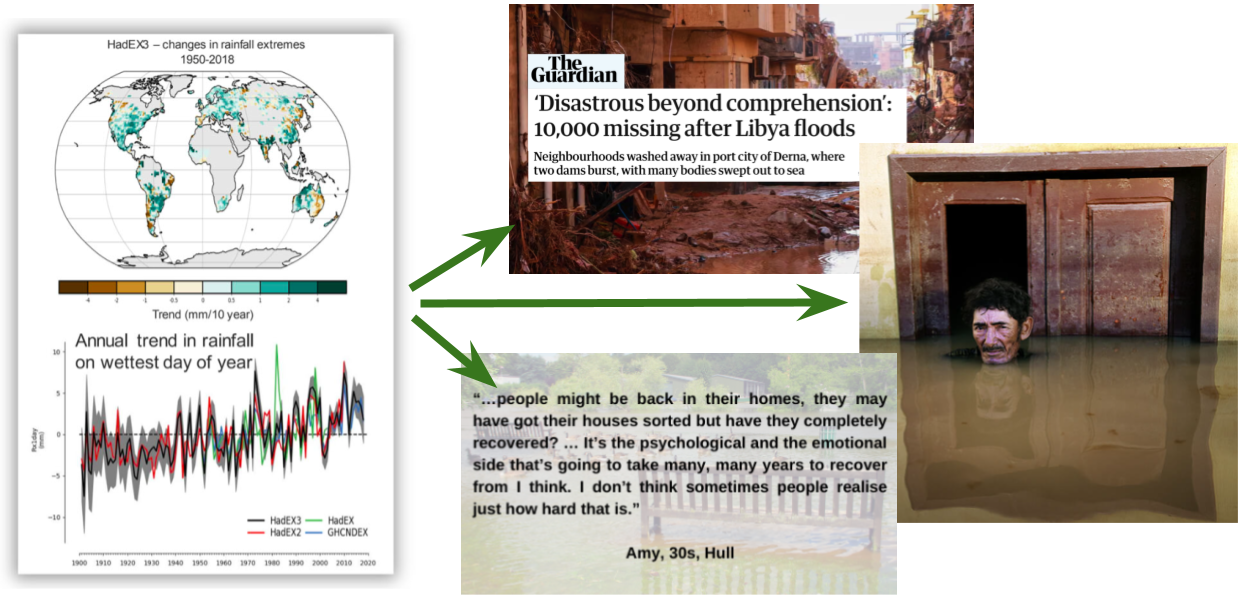

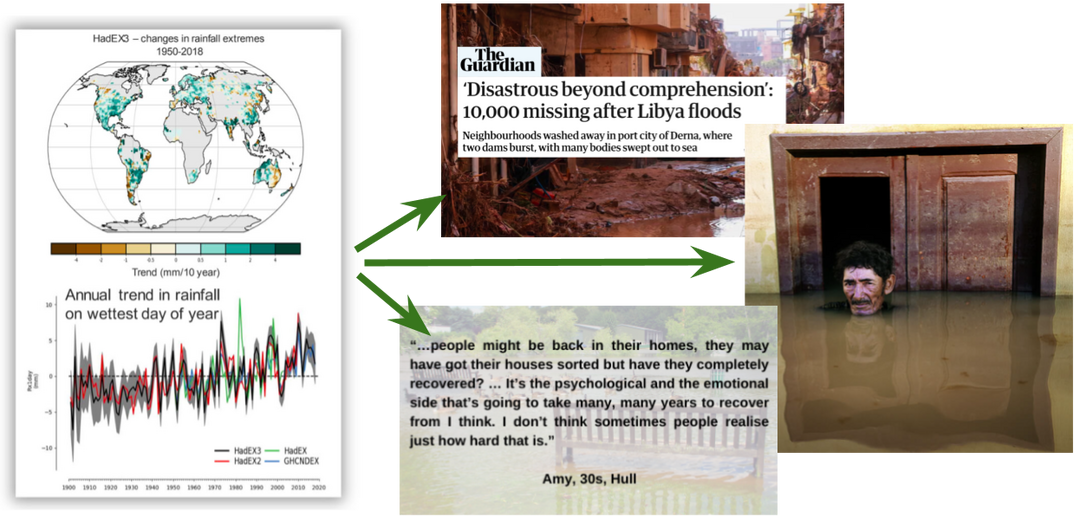

- Show why this matters. Rather than simply stating what the implications are, illustrate it with something tangible to your audience. A photograph or a newspaper headline can communicate instantly what a screen full of graphs never could. Human stories are particularly powerful.

- Share how the knowledge you are sharing has impacted you such as how it’s made you feel and what it’s motivated you to do in response. If this is a step you’re wary of taking, you might consider quoting other people.

- Consider the emotional “journey” of your audience, thinking about how they would ideally come away feeling. I have found aspects of The Work that Reconnects useful inspiration here.

Show as well as tell: Data can be “brought to life” by showing its tangible, human impacts, for example via news headlines, powerful images such as these portraits by Gideon Mendel, and quotes or stories from affected people.

Trust yourself

However many times I do it, and however thoroughly I prepare, I’m not sure I’ll ever feel properly confident standing up in front of an audience and talking about anything, let alone about something as important to “get right” as the climate and nature Emergency. But the risks of getting it not-quite-perfect are far outweighed by the risks of not finding the courage to try. I’ve found it helpful to:

- Be upfront about your knowledge and limitations: You can’t be expected to have all the answers. Communicating about your background, motivations and nerves can help build empathy and trust with your audiences.

- Resist getting defensive or focussing on detracting narratives: When misinformation and even blatant attacks on science are becoming alarmingly normal, it can be tempting to vehemently defend your points, sometimes at the expense of communicating them clearly. My best advice would be to back yourself: lay out the science and case for proportionate action in a compelling way, then be prepared to respond to common delay narratives if they come to you.

What now?

Your communication may be ‘done’ when the audience leaves the room, when your article is published etc… but that’s just the start of the impacts it’ll have. It can take time for people to process the experience they’ve had and what their next steps may be, and in most cases you’ll never know the ripples you create. In some situations it might not be possible or appropriate to “follow up” with audiences but in most cases there are useful things you can do to help enhance the positive impact of your work. These include:

- Providing summary resources that enable audiences to recall, consolidate and feel confident talking about what they’ve learned.

- Sharing your sources and recommendations for deeper learning.

- Signposting appropriate actions, support and community. This helps to guard against leaving people feeling disempowered or alone.

I hope you find this encouraging and informative. I feel conscious that it’s imperfect and non-exhaustive… but that by my own admission that’s not a good enough reason not to share it! Please feel free to contact me if you have suggestions to improve it, or if you’d like to collaborate on future communication projects. 🌱